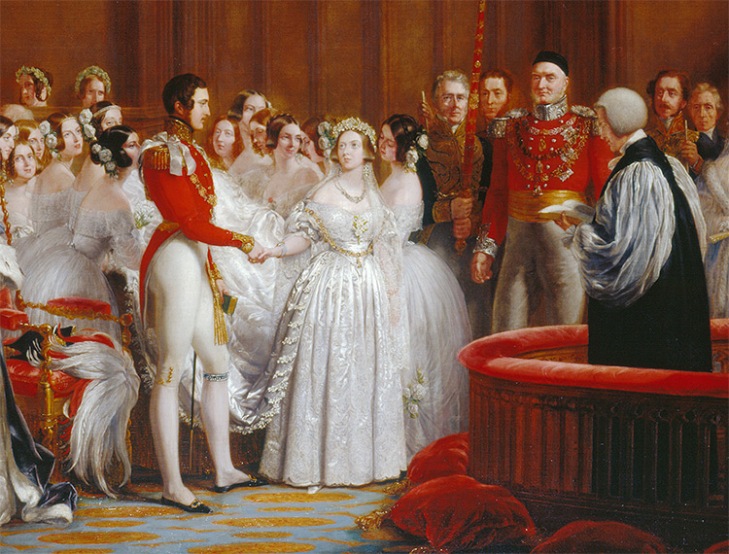

Last week I finished my online course “Investigating the Victorians” through Oxford’s Department of Continuing Education. I was initially drawn to the course because of Victoria, the Grandmother of Mourning. The Widow of Windsor, as she was eventually called, accumulated a variety of reputations over her long reign. I wished to dig into them, to uncover the sort of person she truly was. Many historians write of her withdrawal from society after the death of Albert and of her fastidious obsession with keeping to her outlandish mourning rituals. Some believe she neglected the British Empire in the midst of her agony over Albert’s death. She is chastised for grieving in textbooks and articles on the Victorian Era, even one hundred years later.

An Era of Radical Change and Invaluable Improvements

The Victorian Era was an era of great and radical industrial change. These changes were not always for the better; people had jobs in cities, but their food was of little nutritional value and their air was barely breathable compared to their countryside counterparts, who often outlived them by a good twenty years. Feces leaked into water systems, leading to epidemics such as the infamous cholera epidemic that John Snow traced to the Broad Street water pump. But as the era progressed, these problems brought on by rapid industrialization and urbanization slowly began to be addressed.

By 1901, Britain’s mortality rates had improved (save for infants, unfortunately), in part due to clean drinking water infrastructures and improved labor laws. The Victorians were one of the first societies to treat the insane as patients instead of as criminals. Women were given more property rights and custody rights of their children if they divorced from their husbands. Leisure time increased and religious tolerance grew, turning Britain from an Anglican society to one that was accepting of new religious movements, including Agnosticism and American Spiritualism. Moreover, the only war that marked the era was the Crimean War, from 1854-1856. The Victorian Era, unlike the 18th century before it and the 20th century after it, was an era of peace.

The nation, as I discovered during my studies, did not suffer because their queen was donned in black.

A Queen Inclined to Excess

Victoria was a feisty queen who did what she wanted and when, and bustled about with her “pepperpot” figure, as one British historian so described her in my class readings – she was inclined to overdue things, including eating too much, hence her figure’s tendency to grow horizontally. Perhaps she argued too much. She loved too much and too greatly – her dear Albert’s death broke her queenly spirit, and she mourned him deeply until her own death. Yet even so, she kept herself savvy to the ins and outs of British politics even as she remained a recluse. Her duties were not abandoned during her mourning, they were simply done more privately. Yet to her people and to the elite officials of the government, it didn’t matter, for her “excessive” mourning led them to believe she might very well be going mad.

Melancholy and Madness: Unsuitable Heirs

Victoria inherited a crown that was tarnished. King George III, the “mad king” was her grandfather, and “fears of hereditary madness dominated the Victorian imagination” (Matthew & Reynolds). This was an era, after all, where hysteria, depression after the loss of a child, or even simply a long bout of melancholy could send a woman to the insane asylum. Invalids, the insane, and those suffering from chronic illnesses were discouraged from marrying and procreating, for it was believed these unwanted maladies could be passed down to future children. Victoria’s excessive mourning was interpreted as a sign of possible madness. Fortunately, for herself and for her empire, her mourning did not manifest as madness: “Victoria could be temperamental, passionate, self-willed, opinionated, proud, selfish, obstinate, stubborn, and difficult, but she was not mad. Even after 1861, at the depths of her nervous prostration, she was simply very sad” (Ibid).

Victoria’s Mourning Rituals

Victoria’s mourning was viewed as excessive because “it exceeded the traditional period (which decreed one year of full mourning for a husband, followed by a second year of half-mourning and a lifetime of black gowns and white caps)” (Matthew & Reynolds). This simply wouldn’t do for Victoria; she intended to mourn Albert for the rest of her life. To ensure that the public would never forget the prince whom both they and Victoria were indebted to, “statues [of Albert] were erected by public subscription in some twenty-five cities; hospitals, infirmaries, and museums were given his name” (Ibid). Victoria mourned him daily by adhering to her uniform of black and by secluding herself from society. In every bed she slept in, the photograph of Albert on his deathbed was kept “hung over his pillow,” her very intimate and visceral memento mori (Ibid).

Most peculiarly, Victoria was not inclined to this macabre extravagance when it came time for her own departure from this world.

A Funeral of White and Gold

I was surprised to discover that the Widow of Windsor abhorred what she called “‘black funerals'” and “decreed that her own was to be white and gold” (Matthew & Reynolds). Her funeral was a military funeral, which revealed her commitment to her armed forces, and her coffin “was to be pulled on a gun carriage by eight horses” (Ibid).

She was laid out in her home wearing a white gown, adorned with flowers and mementos that she wished to be placed in her coffin beside her. After her coffin was sealed, it was “encased in a triple coffin of oak, lead, and more oak, weighing half a ton” (Ibid). On February 4th, 1901 Victoria was laid to rest in Frogmore mausoleum beside her beloved Albert.

Victoria was a stable ruler who did not succumb to ignorance nor madness, and who allowed Britain to progress in myriad ways. While her mourning was deemed excessive by some, it was genuine. It was only after her death that she had eschewed her infamous black gown; she was finally at peace.

Source:

H. C. G. Matthew and K. D. Reynolds, ‘Victoria (1819–1901)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2012 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36652, accessed 25 March 2016] Victoria (1819–1901): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36652

Links to photos:

Featured Image via The Telegraph

Enjoyed the article. I read somewhere that Queen Victoria’s mother was a bit of a control freak. I wonder if that contributed to her penchant for excess in her adult life.

LikeLiked by 1 person